Use physics to shape the best bat speed drills to increase power

A lot goes into hitting a baseball. It’s not an easy thing to do. And even when you do make contact, there are nine defenders on the prowl to get you out before you reach the first 90 feet. One thing that can improve your offensive output is to increase your rate of hard hit balls coming off your bat. Having great plate awareness, a good eye, accurate timing and regular contact on the barrel are keys to being a good hitter. But to get the ball to jump off the bat, there’s one attribute that stands out above all…bat speed.

Hitting a baseball, in its simplest form, is a transfer of energy.

How that energy is generated, directed, and transferred is the difference between a weak grounder and a homerun. Or a bunt and a sharp line drive. Understanding how bat speed relates to the hitting outcome can make a big difference in how you train.

History

In a previous article, I explained a bat’s swing weight and how it’s changed over the decades. The way the game of baseball is played has transformed dramatically from generation to generation.

In the early part of the 20th century, power wasn’t considered as important as bat control. There was less emphasis on hard hit balls and more importance placed on controlling where the ball went on the field. Bats were thick and heavy and balls were heavier and less tightly wound than today. Players concentrated on timing the pitch and manipulating the bat to get base hits and doubles. Small ball was king. Homeruns happened but were more often a result of a perfect confluence of events rather than the initial intention of a batter.

1920

That began to change in the 1920s. The ball got more tightly wound and more uniform. Though still heavy by today’s standards, bats transitioned from denser hickory to lighter ash. Small ball was still the primary mode of play, but hitting for power was becoming more of a desired trait in hitters. Players added rudimentary weightlifting to their training, making it easier to swing the heavy lumber. More players were becoming full time professionals, paid enough to concentrate on baseball, even in the offseason. More power hitters emerged.

“Training….had shifted to increase power”

1940

By the 1940s, power hitters were becoming a sought after commodity. Emphasis was still on hitters with a high average, but a player that could hit for average and power was a premium in the lineup. Homeruns were a regular part of every team’s game by now. Training and coaching strategies had shifted to increase power. Pitchers were adjusting their game to keep these hitters off balance, honing their skills with breaking balls and junk pitches, but also to consistently throw harder.

1960

By the 60s, pitchers were throwing harder, and that made their breaking balls more efficient. The differences in speeds made it harder for power hitters to time up the baseballs. The hitters that found success were using different bats than even a decade before. Bat profiles changed to be lighter, with thinner handles. This allowed hitters to swing faster without losing barrel mass. In turn, the faster swings let them wait slightly longer before swinging, giving them more time to identify a pitch before it got to them. And the faster swing was producing harder hit balls when contact was made. Power was there to be had for those that adjusted.

1980

In the 1980s there was a bigger chasm between the small ball and power hitters. You still had plenty of guys hitting for average, laying down bunts, and stealing bases. But you also had more players whose number one job was to hit the ball hard, and preferably, hit it out of the park. These players were valued on how they could change a game in one swing. They were bigger, stronger, and had bats made for their hitting style. Power wasn’t just a novelty. It was essential to ballclubs.

2000

The late 90s and early 2000s saw something that had never happened before. For four straight years*, one or more players hit 60 or more homeruns in a season. A 60+homerun season had only happened twice previously in more than a century of MLB history.

*Obviously, there’s been controversy about that four year span and the players involved. This article isn’t going to judge it either way.*

No matter one’s feelings on that historic period, it had one of the most influential impacts on how the game is played. Because while those balls were leaving the stadium, teams were using technology to better understand the attributes associated with those hits. Science was playing a bigger part in player development. It was providing evidence to better explain the dynamics of a power swing.

At the same time, teams began taking a harder look at available statistics and inventing new ones. These advanced stats started having a bigger impact on how teams were put together and incidentally, how younger players changed their training to be desirable to teams.

“Teams want batters that hit the ball hard.”

present day

Today, we see the result of 100+ years of these changes in the way players approach hitting. Teams want batters that hit the ball hard. Pure contact hitters are becoming rare unless they can back it with power or are exceptionally good at a coveted defensive position. Strikeouts have skyrocketed while offensive output, though dipping slightly from its highs, is still near historical peaks. Batters no longer take a “two strike” approach. Instead, they swing the same with a 0-0 count as they do with a 0-2 count. The reason for that is simple. Teams emphasize hard hit balls and treat a strikeout the same as any other out.

When it comes to hitting at the higher levels of baseball, power is king above all.

That pursuit of power has led to changes in training, equipment, and game study. Bats, and coaching have changed to achieve more power. To achieve that power, the exclamation point has been largely placed on developing one factor…bat speed.

But why?

Understanding energy, force, and power

Concepts of physics can help explain the importance of bat speed.

Kinetic energy (KE): the energy an object has because of its motion. KE=1/2mv²

Force (F): the influence that changes an object’s motion. F=ma

Acceleration (a): the change in velocity/speed of an object over time

Mass (m): the amount of matter in an object. *while differing from weight, for purposes here, assuming objects in the same place have the same gravitational pull, it can be interchanged with weight*

Power (P): the amount of energy transferred over a period of time P=work/elapsed time

bat speed increases energy transfer

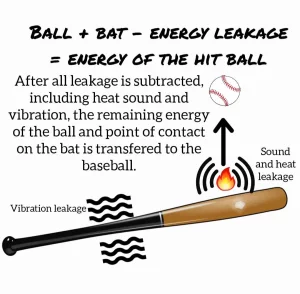

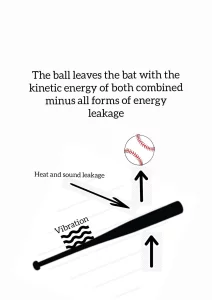

At the collision, there is a transfer of energy. It should be noted, energy can’t be created or destroyed. Instead, it can be transferred from one object to another, stored as potential energy, or converted to a different form of energy, such as light, heat, sound, or vibration.

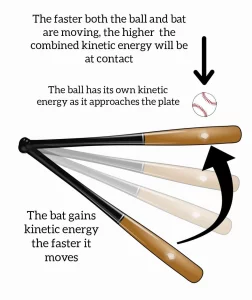

In the case of a hit ball, both the ball and bat have kinetic energy at impact. Upon this collision, the energy of both combine. You see evidence of this in exit velocity (EV) when it’s higher than the speed of the ball or the bat. If no energy was leaked (converted), the energy of both would combine to have the ball leave the bat with the energy that the ball and bat possessed at the time of impact. You would see the result of that in exit velocity. For example, a 90 mph pitched ball hitting a bat moving 70 mph would produce an EV of 160 mph. But that’s impossible in a real world scenario.

Inevitably, no matter how perfectly a bat hits a ball, there’s energy leakage. Energy converts to sound and heat. Some is lost in bat flex and vibration. Even a broken bat is an energy leak.

wood versus metal

With a wood bat, some energy is preserved as elastic potential energy when the ball compresses, then turned back to KE as it reforms. But the ball doesn’t reform perfectly, leaking energy. In fact, the less the ball goes back to its original form, the more energy is lost. That’s why an 8U baseball travels a lower distance than an equally hit tightly wound MLB ball.

A metal bat’s compression is more elastic and reforms more perfectly. It preserves and reconverts energy more efficiently, and the ball deforms less, leading to less leakage. (This is why “shaving” metal bats, allowing more compression, and elasticity is both a thing and illegal.)

What’s left after leakage is then transferred to the baseball. When hit near perfectly, the ball can leave the bat faster than it came in.

You can perceive these energy leaks as a hitter and observer. The crack of the bat. The vibration on the hands. And the travel of the ball.

Because both the ball and bat have energy, the mass, and velocity of both matter for the end result. Baseballs being relatively constant within a given league, the speed of the ball, the mass of the bat, and the speed of the bat’s impact point (ideally the “sweet spot”) are the variables that matter for maximum energy at collision. Of these variables, the ones that matter more are the speed of the ball and bat. Why?

you control the bat

“To increase the energy on the bat, you can raise the bat’s speed.”

Velocity has an exponential effect on energy relative to mass. Kinetic energy is expressed KE=1/2mv². You as a hitter have no control over the speed of the baseball being pitched. But you are in control of your bat. To increase the energy on the bat, you can raise the bat’s mass or the speed of the swing. Every unit of mass added only adds half of itself as a factor. Whereas, every unit of velocity adds the square of itself as a factor.

You, as the hitter, are creating the force on the bat that’s making it move. Force is expressed as F=ma. The force you apply to the bat is equal to the mass of the bat multiplied by the amount you can increase the bat’s speed before the point of contact.

bat weight matters

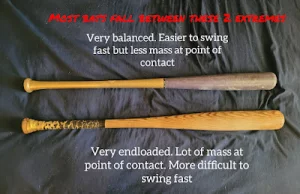

If your force is constant (say, the maximum energy you can provide to move the bat), the lighter the bat’s mass, the higher the acceleration will be. Conversely, the more you add to the mass, the slower acceleration will be. Because the speed at impact provides more energy, it’s more efficient to sacrifice mass for acceleration.

All things equal, the heavier your bat swings, the slower it is going to be at contact.

Power is expressed as P= work/elapsed time. In the case of hitting the ball, the work is the force applied to move the bat from the beginning of the swing to contact and the elapsed time is the time from start to finish of the swing. If work stays constant, the faster the bat can get to the point of contact the higher the power. The heavier the bat, the more work is needed, so at maximum energy expelled, a heavier bat will slow the time for the bat to travel if the same work is applied.

Another factor to keep in mind is that the distribution of mass in the bat will make a difference in energy transfer. The more mass is concentrated at the point of contact, the more it factors into transfer efficiency. There is less leakage from vibration when more mass is behind the contact. You can test this out. If you swing a 5lb hammer at a stake, contact will be more firm and the stake will drive farther than if you were to swing a 5 pound metal pipe at the same stake. With the pipe, you’ll feel more vibration and the stake won’t drive as deep.

Check out this article on the most commonly used bat models.

explaining the sweet spot

Different points on the bat are moving at different speeds. The point an inch above your hands is moving slower than the point at the end of the bat. Why? Because the bat is a rigid object and stays straight through the swing, the point above the hands is traveling a shorter distance in the same amount of time the end is moving a longer distance. The end of the bat has more velocity.

So why does a ball hit off the end of the bat come off weak? Kinetic energy and leakage. The end doesn’t have enough mass concentrated at that point, only speed. And because the end isn’t a stable point, there’s more leakage through vibration. (That’s why bats often break when hit on the end.) Remember kinetic energy is the combination of mass and speed. The sweet spot is the ideal place to contact the ball because it’s got a large enough concentration of the bat’s mass to transfer the most energy while being close enough to the fastest part of the bat to maximize KE. The sweet spot is the point that has the highest kinetic energy on the bat.

Kinetic energy, force, and power all take the mass of your bat, and the speed it can be swung into account.

The goal is to hit the ball hard. That means using force as efficiently as possible with as much power as possible to provide as much kinetic energy in the bat at collision as possible.

You are the power source for bat speed

While these principles can explain what’s happening with the bat and ball, they also apply to you as the hitter. After all, without you, the only force being applied to the bat is gravity.

You are the source of energy to move the bat. You take force from the ground through your legs, apply it as torque to your torso and direct it through your arms, wrists, and hands to the bat. There are a lot of linear and rotational forces being applied by you in less than a second. And each of these movements is a transfer of energy.

Torque: the measure of the force to cause rotational movement

Your swing is a complex system of simple machines. In short, simple machines multiply the force input to create a higher output. Examples of these levers within the swing are the levers of your legs, the screw of your torso and shoulders, and the levers of your wrists and bat. When everything in the system works optimally, the force started at the feet continues to multiply to exact maximum energy to the sweet spot of the bat at impact.

How you harness that energy, how much capacity you have to transfer energy, and how efficiently you can deliver that energy to the bat all make the difference in a middling swing and a power hack.

you are in control

These are all factors that you have some degree of control over.

“Your strength factors into how much force you can deliver”

Your capacity is what output you can create with your body. Some attributes, such as your height and arm length, are beyond your control. Your strength, flexibility, muscle type, and muscle control are all factors you can train, though. Your strength factors into how much force you can deliver. Your flexibility contributes to elasticity (potential energy you can store). There are 2 main voluntary muscle types and which one you prioritize in training aids either endurance or, more important to bat speed, strength, and speed. Muscle control is using your muscle efficiently for movement.

By getting stronger overall, increasing muscle flexibility, prioritizing training type II muscles, and learning to move optimally, you can greatly increase the force you can apply to the bat.

Your body is an energy factory

Energy is always being taken in, converted, and transferred. The beat of your heart, the synapses in your brain, food digestion and everything else going on inside is energy conversion.

The primary fuel your body uses for movement is glycogen. When you eat, your body breaks down the food into glucose, proteins (amino acids), fatty acids, and waste. Your body then uses these for various processes. Proteins are used for repairing cells such as the muscle fibers broken down during a workout. Fatty acids aid body processes and extra is stored in fat cells to be used as needed, whether to replenish fatty acid levels or go through a process that turns it into glucose (this is how a diet can make you lose fat, by the way). Glucose is converted into glycogen and stored in the muscles to be used as energy fuel.

how training transforms you

When you train for strength, you are breaking down muscle fibers. During recovery, proteins and anabolic hormones go to work to rebuild those fibers. And they rebuild them in a way to be able to withstand the forces that broke down the fibers previously. (For reference, this is how anabolic steroids are illegally used for performance enhancement.) Through progressive overload, adding work through more weight or reps, muscles gain the capacity to exert more force. At the same time, the muscles gain more capacity to store and use glycogen.

To train type II muscle, commonly called fast twitch muscle, you have to push the muscles to their boundaries in training. This means creating more work through heavier exertions or faster movement. Sprinters, type II machines, don’t get faster by running a marathon. They get faster by pushing themselves through short sprints or adding weight while sprinting. They are concerned with exerting more force in a short time, not how long they can exert that force. Likewise, hitters should concentrate on their ability to exert maximum force over a short time span.

get your flex on

Flexibility has multiple benefits. The more flexibility a muscle has, the more range of motion it can go through. The longer range of motion allows for more energy to be transferred. Flexibility also adds to a muscle’s elasticity. Elasticity is a form of potential or stored, energy. It’s like a rubber band. As you pull back a rubber band, the potential energy in it increases until you let go, it converts to kinetic energy and flys. The farther you pull back, the farther it flys.

“When you train a movement properly, you’ll adapt…”

stay in control

Muscle control is teaching your body to do certain movements. Your brain and nervous system control your muscles. When you first try to do a task it’s often difficult and sloppy. But the more you do it, the more your system adapts to it, making it easier to do. This can be beneficial but can be detrimental, too. When you train a movement properly, you’ll adapt and over time become more efficient at it.

If you train a poor habit, however, you’ll adapt to it too. And it becomes harder to “unlearn” that bad habit. Train properly from the start whenever possible. This is where practice is so important.

The bat will do what you force it to do. It’s up to you to learn how to make it do what you want to.

How to apply all this to your swing

To hit with power, you have to consider your bat speed. Taking the science into account when developing your swing can help with every aspect of the action.

Creating efficiency of movement, optimal transfer of energy, applying maximum force and squaring up on the baseball all take time, practice and patience. But it also helps to have an understanding of the underlying actions taking place, along with why certain things help or hurt.

This section isn’t a substitute for a hitting coach. It’s to help identify places where you can examine to see if you can improve your movement for maximum output.

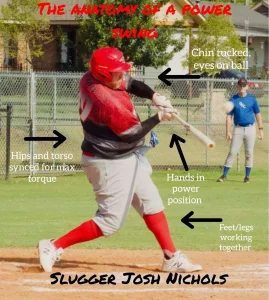

A power swing is going to have efficient movement from foot to barrel. It’s going to utilized your body to its highest potential to turn the force you provide into maximum kinetic energy at contact.

“Energy loss is the killer of power.”

Every movement is going to have the potential to multiply force applied or leak energy. Energy loss is the killer of power. For the best possible result, every move must be coordinated to the next in a chain reaction.

Maximizing mechanics

It starts at the base, your feet. Getting a good relaxed stance to transfer momentum. Not too tense but not lazy either. As the pitcher goes into the windup, you begin your load. Shifting the weight back on your back leg, torso slightly turned away and bat up and back. The load is you harnessing potential energy. Your muscle fibers are pulled back adding elasticity. You are ready to let go of the rubber band.

As the pitch comes, you begin to shift your weight forward (linear force), while your hips, torso and upper body are still loaded. Your front foot hits firmly and drives force back up the leg to the front hip, driving it back. All the while, your back leg is push upward into your back hip, driving it forward.

This creates the torque in your hips to rotate while your torso and upper body are still loaded. Then your torso fires rotationally, letting go of the rubber band and adding addition force through muscle contraction in the front side muscles. As your torso rotates your shoulders rotate together adding to the torque. Your back arm begins to extend, adding more linear force. Your wrists snap, adding even more force.

All the while, your bat is moving. First forward through the weight shift, then rotationally on multiple axis as your torso turns, gaining speed as you move your shoulders, arms and wrists and finally, hopefully reaching maximum velocity at the point of impact.

In less than a second, a complex system of simple machines has been unleashed. Seems simple, right.

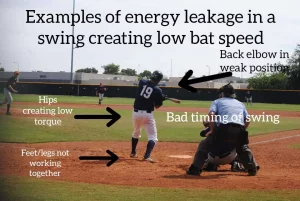

bad mechanics will decrease power

Unfortunately, as with all complex systems, any inefficiency at any point will sap the effectiveness of the system. Every component has the capability of multiplying or draining the energy of the final output. When every part of your swing is working together, firing in the right order, at the right time, and with the most efficiency of energy transfer, your hitting power will be at your maximum. But if any single part of your swing is off even a small amount, your power potential decreases drastically.

This is where individual training, coaching, practice and self examination come in.

If you want to swing with more power you need more bat speed. Physics demands it.

Ways to increase your bat speed

⚾️ Lift weights.

Build overall strength. Use a balance of heavy weights, proper form, and full range of motion. Alternate periodically between a concentration of heavy weight and fast movement.

⚾️ Increase flexibility.

Use static stretching, active stretching, and myofasial release to increase range of movement and muscle elasticity.

⚾️ Optimize your swing mechanics.

If needed, find a knowledgeable coach to help you identify where you are leaking power. Get rid of unnecessary movement. Don’t cast, loop, or separate your hands from the upper body too early. Your bat will have a natural arc through the swing but your hands should move on a straight line from load to intended impact.

⚾️ Swing with different weighted bats with various weight distributions.

Use a hands trainer (heavy close to the hands) to work of strength in getting your hands to point of contact (horizonal swing strength). Use a heavy end loaded bat to train driving the bat head through the zone more quickly while keeping it on the proper plane (vertical swing strength). Use a light bat to let your muscles adapt to a faster swing movement. Use your regular bat the majority of the time, concentrating on swinging as fast as you can without sacrificing proper mechanics.

⚾️ Do batting practice facing various speeds and locations.

Don’t only practice your swing when the location is ideal. Your mind and body need to practice adjusting to hitting in different locations and at different speeds to feel comfortable swinging at maximum effort.

⚾️ Choose the right bat for you!

Remember, power is about maximum kinetic energy at collision. Velocity and mass work together. Having the right balance of bat mass and bat speed is necessary to maximizing KE.

⚾️ Have fun through the process. When you enjoy what you are doing, you will put in better effort and have better results.

⚾️ Recover. When you are training hard, recovery is necessary to build whether it’s strength or speed.

Bat speed is only one factor

Bat speed is one of the most important components of hitting for power. But by itself, it won’t make you a good hitter. After all you can swing the bat a million miles per hour, but if you can’t make contact it’s still going to be a strike.

Bat speed won’t give you a good eye. You still have to choose which pitches to swing at. You still have to identify their speed, location and trajectory. And you still have to time your swing to hit the ball. But having better bat speed will give you more time to calculate.

“Hitting a baseball is predicting the future.”

Bat speed won’t square the ball up for you. Hitting a baseball is predicting the future. No, really it is. You are not swinging at where the ball is when you decide to swing. You are swinging where you predict the ball will be when it eventually reaches the plate. The accuracy of your prediction is determined by your ability to process the information you see in a couple hundredths of a second. Yes, hitting a ball squarely is very hard to do consistently.

Great bat speed won’t do you any good if you don’t also work on good awareness, pitch selection and timing. It’s a major component of your overall hitting profile. It should be trained constantly. But it must be integrated with a well balanced hitting strategy to have the most benefit.

⚾️⚾️⚾️

Hopefully this article can help you find ways to increase your power. If you have any questions or responses, comments are welcome. Keep working on your game whether you are 14, 44, or 74. Swing away and have fun!

And hit the ball hard!

⚾️⚾️⚾️

Play ball

This article was originally published on The Middle Age Amateur Ball Player.